It was late August, and students returning to Georgetown from their summer vacations were shocked to find that the campus party scene had become the polar opposite of what it had been only the previous spring. The administration had introduced a new drinking policy, eliminating the tacit approval that students had long felt they had received from the school to work hard and party harder. Suddenly, Georgetown students faced keg limits, party registration deadlines, and ominous sanctions against anyone who facilitated underage drinking. Student resentment grew as campus security gained notoriety for party-busting, and the party scene languished, culminating in student protests. The administration, students felt, hadn’t just made it harder for underage drinking to take place—the administrators had violated Georgetown’s very culture.

Although these events might seem familiar to students who returned to campus for the fall semester of 2007 to find that the administration had enacted the latest version of its alcohol policy, this was the state of Georgetown twenty years earlier, in 1987. After the drinking age in D.C. had risen from 18 to 21 the year before, the University introduced a new comprehensive alcohol and drug policy, which forced Georgetown’s drinking culture to change dramatically.

“Have you ever seen that show Mad Men? It [was] like that,” Rick Newcombe (COL `72) said of Georgetown before the policy changes.

Students, who until then had been accustomed to a campus where it was acceptable to spend Saturday afternoons casually drinking on Healy Lawn, were incensed. It was as if a university full of collegiate Don Drapers had suddenly been told to eschew the three-martini lunch. Georgetown’s campus, as described by alumni and newspaper articles from the 1970s and 1980s, was more akin to the fictional Faber College of Animal House than today’s stately Georgetown. Before the introduction of the 1987 policy, the University had barely any alcohol restrictions in place, and binge drinking was omnipresent. But the biggest difference between the Georgetown of today and the Georgetown during those two decades was that students’ over-indulgence took place in plain sight. Then, it was common for Copley residents to advertise their parties by hanging painted bed sheets out of their windows, and drinking was integral even to freshman orientation. The University, it was understood, paid little mind to students’ drinking habits. For years after the District passed a law that banned the sale of hard liquor to minors in the ‘70s, Georgetown allowed student clubs to flaunt this rule at their events—nearly all of which offered alcohol.

The result was ubiquitous drunken behavior. Students were so abusive of visiting fans and sports teams at on-campus football games that in the early 1970s, teams began to refuse to play against the Hoyas. At times, student drinking reached worrisome levels. An article that appeared in the Voice on April 25, 1978 cited two startling incidents—a student’s plunge from a four-story roof into a pile of debris (he survived), and a student government senator allegedly set fire to his room while intoxicated—as evidence that Georgetown had a drinking problem. Resident Advisors found that they were unable to prevent students, returning from bars, from opening fire extinguishers, wantonly destroying furniture, and ripping drinking fountains from the walls; so R.A.s began to entreaty Georgetown University Protective Service (now Department of Public Safety) officers to station themselves in hallways on weekend nights.

“It was wild and crazy,” former Voice staffer Marty Yant (SFS` 71) said.

Although the school hired an alcohol counselor in 1978, the University did little to discourage drinking in the decades between 1966—when they first allowed alcohol in some dormitories—and 1987. Administrators frequently told the Voice and the Hoya that Georgetown had a “very real” alcohol problem, and a few administrators campaigned against drinking at sporting events and the Senior Week Bar Crawl. Burgeoning worry among administrators and the alcohol counselor’s estimation that ten to fifteen percent of the students he saw had developed serious alcoholism, however, never translated into successful efforts to curb student drinking. Even when, in 1977, the Senior Class Committee stopped sponsoring the Bar Crawl–in which seniors competed to drink at as many different bars on M Street and Wisconsin Avenue—the Crawl continued unofficially for years. As before, the prize for winning was more alcohol. The main obstacle to retraining student drinking, most administrators agreed with resignation, was that it had been the centerpiece of Georgetown’s leisure culture for too long.

“I don’t know whether that’s due to its Irish-Catholic background or what,” Associate Dean of Students William Schuerman told the Voice in the same April 25, 1978 article. “There has always been an open attitude toward drinking at Georgetown.”

***

Schuerman didn’t know his Georgetown history: in the early nineteenth century there was little evidence that the all-male campus would ever become a site of epic revelry. In fact, for most of the University’s existence preceding the fete-friendly ‘70s and ‘80s, student life was extremely regimented. Any number of rule infractions, including possessing tobacco, earned a student “jug:” detention in the tower of the Old North building, where students were forced to memorize Latin verses. Students who tried to get away with much else were summarily expelled. Into the late 1800s, Georgetown dismissed students so frequently that any student who didn’t live in the area was appointed a guardian, who would take him in the event that he was “rusticated.”

It was not until Father Patrick Healy became the President of Georgetown in 1874 that Georgetown abandoned its most stultifying rules. The 1895-1896 rulebook reveals that forays into the city resulted in Latin lines, not expulsion. The University might still dismiss students who were caught drinking or who roamed off of campus too frequently—like the student who was expelled for being “in a St. Patrick’s Day Rumpus” in 1908—but the school gave drinking tacit recognition as a reality of student life. In his history of Georgetown entitled Early Student Customs, Curricula, and Relaxations, William Devaney wrote that “the day after St. Patrick’s Day [became] a good bet for a [school] holiday.”

All of this time female students were missing from Georgetown and students’ social lives. With rare exceptions, University Archivist Lynn Conway said, women did not comprise any part of the student body until Georgetown established the School of Nursing in 1903. The introduction of female students precipitated the relaxation of Georgetown’s alcohol and leisure rules. Male and female students began to enjoy an integrated social life at dances and stealthy trips to local bars. Under the 1903 rulebook, “students in good standing” could get permission to stay out until midnight. The School of Foreign Service and the University’s Graduate Science program began accepting female students in the 1940s, and within a few years students were lobbying the school to increase the number of rooms in which clubs were permitted to serve punch and beer.

Around two decades later, in 1966, Georgetown became the first Catholic university to allow male students to keep alcohol in their (still gender-segregated) dormitories. The change, which Student Personnel Director Father Anthony J. Zeits explained, was an effort to “develop greater responsibility among … students,” surprised many: three years earlier, a November 21 Hoya article reported that the University had told male students living in New South that the building “was architecturally inadequate for the possession of liquor and the admission of girls.”

After three years Georgetown evaluated its decision to allow alcohol in dorm rooms. The findings were robustly confident. Dr. Donald R. Bruckner, who was in charge of an independent study of the change, found that allowing alcohol in rooms had not increased drinking in the dorms or interfered with students’ academics. Delighted administrators published a summary of the findings straightaway in a boastful press release: “Lifting of Dormitory Drinking Ban Successful.”

It was successful, but not in the sense Bruckner and the University meant. Immediately after Georgetown allowed alcohol in its dorms, illicit activity exploded into public view. Yant, the Voice staffer, said that Georgetown changed so significantly from 1967 to 1968 that “it was like somebody flipped a switch.”

“Drugs started to be openly discussed and used. LSD was big, marijuana of course … [Alcohol] and puke were everywhere,” he said. At a Christmas party the Voice held in McDonough Gymnasium, Yant recalled seeing “one of the Jesuits there, as drunk as the rest of us.”

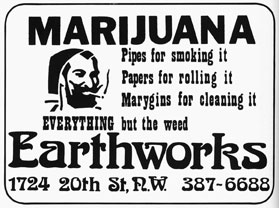

For their part, the Hoya and the Voice took turns making rough estimates of student drug use. (Or encouraging it: in its ninth issue, the Voice printed several recipes that called for marijuana, including pot roast, hash brown potatoes, and marijuana mushroom soup.) The two papers may have disputed the number of students who smoked pot, but both agreed that it was extremely common, while narcotics use was rare. But the fascination of students and campus newspapers with drugs was short-lived. In 1975, the Domesday Booke wrote, “The uproar that drug use caused has settled down into a mellow cloud of pot and hash … as students return to enhancing the University’s reputation as the ‘drinking man’s school.’”

***

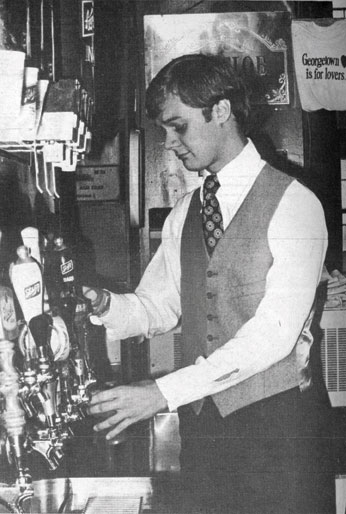

It would be over ten years until this reputation would be in jeopardy. Most other nights in 1987 Mark Corallo (COL `88) would have been working exhaustively behind the counter of the wildly popular University Center Pub to accommodate a line-out-the-door crowd. The Pub, a student-run bar in the basement of Healy Hall, which former General Manager Corallo recently recalled as being “sticky, smelly, sweaty, [and] time-of-your-life,” had served as the epicenter of the “drinking man’s school” for nearly thirteen years. In the fall of 1987, however, Corallo felt that the Pub’s place in Georgetown’s culture, along with its balance sheets, was in serious jeopardy. This was thanks to a part of the University’s new alcohol policy, which required the Pub to host “dry nights” every Wednesday for freshmen who couldn’t drink. And so on a Wednesday in late September, Corallo headed not to the Pub—which, being dry, was also empty—but to Gaston for a town hall meeting, where members of the administration explained the new rules governing drinking. He joined over six hundred other students there to protest.

The University had organized the town hall in response to the students’ anger over the new drug and alcohol policy, which had been building for weeks. The policy had not just levied new conditions on student drinkers, it had done the unthinkable: it had made drinking a punishable offense for the first time in recent memory.

The biggest affront of the new, more stringent policy was that three-quarters of students were still of legal drinking age under a grandfather clause in the District’s drinking law. Alumni recall the policy’s effects as both immediate and shocking. No one any longer believed in the popular campus saying, “you can roll a keg onto Healy lawn and start a party, and no one will stop you.”

Compounding students’ indignation was the the policy’s timing. The District had raised the drinking age in October of 1986, but the program’s architects—the Drug and Alcohol Task Force–first met in April of 1987, when students were preparing to go home for the summer. When they returned and the school introduced the policy as a finished product, the students charged that the administration had circumvented campus input on purpose—a charge many students would echo in the fall of 2007 when they returned to campus and were surprised to find the alcohol policy significantly stricter than before. As a result, the policy’s designers caught even more heat than they were already in for. All over campus, students maligned one person in particular who they felt was accountable for dismantling Georgetown’s campus culture: then Dean of Students John DeGioia.

It was, after all, DeGioia’s office that had chosen the members of the Task Force, who approved and announced the policy, and it was DeGioia who took the blame for the lag between the change in the District’s drinking age and the assemblage of the Task Force. According to a September 24, 1987 Voice article, at the town hall meeting he called the delay a flaw in the policy’s design, and said it “violated the fundamental principle by which I run the department.” Most students felt that DeGioia had handed the decision over to faculty members who had long wanted to improve Georgetown’s drinking habits, even though the Task Force had been charged only with responding to the change in the drinking age.

Renee DeVigne, who was a member of the Task Force and the former Assistant Dean of Students at Georgetown, disagreed with this characterization.

“If students perceived a Draconian change, it would have been a product of the University’s reaction to the drinking age change …. We had no choice but to react to the law,” she said.

Students’ skepticism of the administration’s motives, however, may not have been without merit.

“Some [administrators] had the sense that this wasn’t just about Georgetown’s responsibility to change with a law; [it was] about: ‘does Georgetown have a drinking problem?’” Gregory Smith (COL `88), who was President of the Georgetown University Student Association when the Task Force met, and one of its three student members, said. “There were members of that Task Force that showed up thinking that Georgetown needed to be a dry campus.”

Smith argued, though, that the resultant policy would have been much harsher had DeGioia not ensured that the Task Force included students.

“Jack DeGioia had the guts to tell the faculty that there needed to be student involvement. If it weren’t for him, [a Jesuit] would have been the only other person on the Task Force who would have been living on campus, in reality,” Smith said. “The only reason there was any drinking on campus was because of [DeGioia].”

In the end, Smith said, student members of the Task Force agreed with the faculty that the new policy was a reasonable reaction to the new drinking age. But whether or not it was the policy architects’ intention, Georgetown’s brazen drinking days were over. The Pub became the policy’s first high-profile victim. Corallo said that being forced to go dry one night of the week sent its books into the red, and Vice President of Student Affairs Dean Donahue ordered that it close within two years.

High times: In the 1970s the Voice ran ads like this and printed recipes for pot roast, hash browns and marijuana mushroom soup.

Dave Cannella (COL `90) said that one unintended consequence of the new policy was that it forced drinking to go underground and further off-campus. Drinking could no longer take place in plain sight, and party sizes shrank precipitously. The policy became a model on which all subsequent policies have only varied. It essentially seems to have made the campus party scene what it is today: clandestine, confined mostly to townhouses and University apartments, and extremely annoying to Georgetown residents living near campus. Articles from the early ‘90s indicate that increased party noise from student houses in Burleith and West Georgetown significantly worsened the already-present town-gown tensions.

Whatever excessive partying survived throughout the ‘90s died with the abolition of Block Party, a charity barbecue and boozefest which traditionally took place in the streets of West Georgetown. In 2000, Vice President for Student Affairs Juan Gonzales made a show of withdrawing official University support for the Block Party to appease increasingly testy neighbors. Despite Block Party organizers’ protestations that the event had never needed University support in the past, Gonzales’ move succeeded in putting an end to the event. When the University offered to replace it with an on-campus party, students were unable to meet the stringently high conditions the University set for such an event. A small group of students tried to recreate Block Party in the streets of Georgetown anyway; five were arrested for open container violations by the Metropolitan Police Department. Block Party was dead, and so was Georgetown’s Bacchanalian heyday.

Great article. Despite the stringent alcohol policy, I do have memories of some particularly awesome dance parties sponsored by WGTB and the Voice. It seems that the right combination of people, a sufficiently small space to encourage sweaty revelry, and sufficiently fantastic music can make up for the University’s policies. At least for the 3 hours until DPS or MPD broke it up, anyway.

okay, so it seems that the liberalization of the alcohol policy led to an increase in not just drinking, but also excessive drinking. Why then, do so many students try to claim that a stricter alcohol policy will push people to drink more off-campus? not all that much has changed (in the way of alcohol that is) in the past two decades.

This is an interesting article and it seems to show that tough policies actually can be an effective way to fight underage drinking. However, I feel that to truly stop underage drinking in America, a larger cultural movement encompassing parents, adolescents of all ages, various forms of media, etc. will be needed. Colleges and universities can only do so much by themselves.

The Alcohol policy continues to side with neighbors and less with students. Students only last 4 years, neighbors and administrators are here for decades. The solution is to stand united and firm. The University responds to money, what if all party inclined Hoyas refused to donate till the school gave us more options. SNAP is the newest problem. Students are being forced to binge drink in dorms, get fake ID’s, and move farther off campus. The farther we roam, the less safe it is. Dear GU: Stop limiting your students, start caring about more than your appearance to the neighborhood, and please please start listening to students more than anyone else.

Interesting history When i was at GU in the dark ages ie late 60’s the drinking age in DC was 18 for beer and wine. About 15 years ago there was an article in the Wash Post about alcohol and college students. In my profession I do see alcohol as a real problem especially with young adults. However the article pointed out that the culture of drinking had seemed to change. In the past, alcohol was part of the socially acceptable culture with college students. It was used in socially acceptable situations. For example, a professor would have students over to discuss some issues and wine would be served. Part of the problem today is the secret nature of alcohol. It is taboo and thus that may contribute to not so good ways of drinking. I do remember having a chemistry small group discussion on Healy Lawn with our grad student and having beer which i didnt like with lunch. just a thought but i always felt that that Post article made a very good point. Young adult and or teenage drinking is a huge problem which we havent really been able to address to help those who really have a problem with alcohol. It does interest me at eighteen you can vote , get married , have kids, and even die for your country in a war but NOT have a glass of wine or a beer. Just throwing that out there, It IS about much more than just the bball.